The president is having a mental breakdown in “Symphony of Rats,” a 1988 fever dream by the inveterate theatrical bad boy Richard Foreman. But the strung out commander-in-chief doesn’t look quite as unhinged as he once did.

For that you can thank Donald Trump, who has lowered the bar for presidential behavior. The idea of a former president mouthing off on the campaign trail about the impressive genitalia of a dead golf champion — well, it’s clear that 21st century reality is giving Foreman’s ontological-hysteric aesthetic a run for its money.

The Ontological-Hysteric Theater is, of course, the name of Foreman’s experimental company, and it’s instructive to consider the two words in proximity. Ontology, or the metaphysical consideration of being, was always at the core of Foreman’s theatrical explorations. And hysteria, marked by uncontrolled emotion and frenetic excitement, was the manner in which these investigations into consciousness were conducted.

The Wooster Group collaborated with Foreman on the original production of “Symphony of Rats,” an occasion in which the Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse of New York’s downtown avant-garde performance scene teamed up. Foreman directed that premiere, working with Wooster Group ensemble members, including Kate Valk, who is now co-directing this deconstructionist revival with Wooster Group leader Elizabeth LeCompte.

If the version of “Symphony of Rats” that is playing at REDCAT (through Wednesday) is more Wooster Group than Foreman, there’s enough of both to delight and derange the theatrical senses.

Foreman and the Wooster Group share an aversion to linearity, psychological realism and didacticism of any kind. Collage and collision are their preferred multimedia modes. They reject straightforward representation in their theatrical design, creating surreal universes of their own rather than adding to the store of knockoffs of the known world.

After a decade and a half of seeing everything I could of Foreman and the Wooster Group in the 1990s and early aughts, I came to appreciate the essential differences between these two artistic trailblazers. Lurking behind Foreman’s madhouse phantasmagorias is the mind of the artist interrogating its own secret chambers. Beneath the layers of the Wooster Group’s postmodern antics, on the other hand, are only more layers of performance. There is no single consciousness beneath the work. Reality itself is a form of theatrical interplay.

The Wooster Group — and, by the way, it’s great to see the company back in its L.A. home — operates on a group dynamic. Foreman, who wrote, directed and designed many of his own productions, is more of a collaborative autocrat. His presence in his work is inescapable. (In his production of “Symphony of Rats,” the face of the outer-space creature conferring with the president was Foreman’s own.)

Foreman, who is 87, gave his blessing for Valk, LeCompte and the company to make the piece their own. And they’ve done just that.

Ari Fliakos plays the president. He begins this new production by relating a fever dream he had after being vaccinated for COVID-19 and the flu. This anecdote conflates the psychedelic trip that his character undergoes with the actor himself. It’s as though Fliakos is simultaneously having a meltdown with the president. The ensuing spectacle is mesmerizing.

The president is receiving doom-laden messages he believes are from outer space. Naturally, he’s worried about the state of his mind. “My mental Polaroid is broken,” he says. “I snap a picture, but nothing happens.”

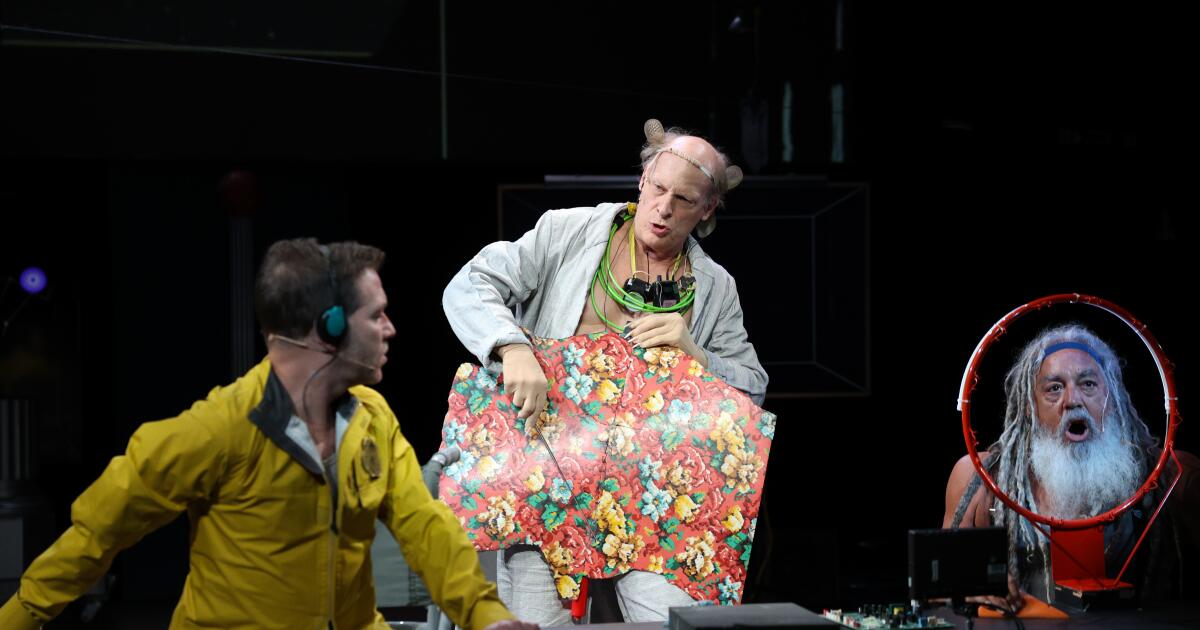

He’s surrounded by forces that seem determined to tip him permanently over the edge. Jim Fletcher, kitted out like a mad scientist on a retro electronics kick, shadows the president as though he were prancing around in his twisted dreams, sometimes in the guise of an unusually tall rodent.

Seated at one of the Wooster Group’s signature conference tables and speaking through a basketball hoop, Guillermo Resto intones admonishments in Darth Vader tones. Niall Cunningham ministers impishly to the president, preparing him for the next phase of his hallucination. A female figure on screen expands the madness to the digital cosmos.

In his published introduction to the play in “Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater,” Foreman notes that, when he directed the Wooster Group actors in “Symphony of Rats,” he was aiming for a more “subdued, internalized performance style” than was customary for the troupe. He wanted the president (played by the fearlessly irrepressible Ron Vawter) to be clearly working out his own mental conflicts. For Foreman, the politics of the play comes down to the fundamental question of “managing noise,” which is to say ambiguity, in psychic life.

The Wooster Group version is a far cry from the “sober” and “emotionally self-contained” vision that Foreman claimed he was after. The world of the play is one of sci-fi satire, underscored like a merrily suspenseful summer blockbuster. It is a world of cinematic quotation, in which “Women in Love” is juxtaposed with the gory action-comedy antics of “The Suicide Squad” and a sequence from Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator” is reenacted for resonant kicks.

It is also a world in which digital personae appear ready to lure the unsuspecting to places they may never return from. Blurring the line between humans and technology has long been a Wooster Group specialty. This production of “Symphony of Rats” made me long for the company to tackle in a sustained way the coming storm of artificial intelligence. Here, there are glimpses of its possible impact on the stability of human identity.

This Wooster Group offering moves the company closer to conceptual installation art. The work proceeds as a series of movements, one vignette succeeding the next in a way that can feel static from a dramatic standpoint. By the time we get to the “Tornadoville” sequence, we could be anywhere — or nowhere.

The locus is always the president’s unspooling brain, but the precise navigation is left to the actors. As captivating as Yudam Hyung Seok Jeon’s video and Eric Sluyter’s sound design and music are, it’s the hypnotic individuality and exemplary discipline of the performers that seize our attention.

Trying to make sense of “Symphony of Rats” is like chasing after a stranger’s dream. But sense is overrated with actors who can overcome all sensory competition through the singularity of their art.