“Life on Earth: Art & Ecofeminism” is a somewhat difficult exhibition to grab hold of, but that’s mostly because its important subject is so much larger than a diverse but relatively modest presentation can encompass.

Ecofeminism rejects the idea of human dominance over nature. The inaugural show at the Brick, an independent art space formerly known as LAXArt and recently relocated to Western Avenue, features 18 works by international artists and collectives that touch several intriguing bases of ecofeminist art launched since the 1970s.

Insistence on the supremacy of people over the natural world is cited as the primary source of environmental destruction. Furthermore, the practice is tightly bound to the seemingly intransigent social marginalization of women. Remember Mother Nature? If we insist on regarding the natural world in such feminine terms, then authority over women is an essential — and equally destructive — corollary to authority over nature.

The show’s earliest piece might be an analogy for the whole. In 1972, when Aviva Rahmani was a student at the California Institute of the Arts, she directed and documented in slides a performance titled “Physical Education.” Filling a plastic bag with tap water, she and a performer drove 50-plus miles from the suburban school in parched Santa Clarita to the Pacific Ocean, stopping four times along the way to deposit teaspoons of water on the side of the road, then replacing each with a spoonful of dirt.

When Rahmani got to the beach, the muddy bag was emptied out in the sand and refilled with sea water. She promptly drove it back to CalArts, reversing the process. Upon arrival, she flushed the dirty water down a toilet.

In the exhibition, a cycle of elemental return and fundamental waste unfolds in slides projected from an automated tray onto an ordinary freestanding screen. The setup, common for pre-digital Conceptual art, is much like the way folks used to show the neighbors happy pictures of their summer vacation. Here, water transport assumes a form that is grandly ritualistic if decidedly prosaic.

None of the individual photographic images in “Physical Education” is especially distinctive. The artful feature of the work is instead embedded in the installation’s composition.

Rahmani’s pictures don’t come close to filling the screen, although they could easily have been projected that way like snaps from the family trip to Disneyland or Yosemite. Rather, they nestle down in a corner, modestly flashing by, one after the next, as the slide tray clicks in nonstop rotation. The mostly empty screen’s larger blankness implies that there’s plenty of room for many more pictures awaiting exposure. This work of ecologically minded art is positioned as just one self-aware fragment of a much bigger worldview that needs to be seen as holistic and systemic.

Nearby, a pair of large, documentary performance photographs made five decades later by L.A.-based yétúndé olagbaju resonates against Rahmani’s historical piece. At left in “protolith: heat, pressure,” the artist is seen from behind, dressed in a white robe and headscarf. They emerge from within a rocky outcropping in an otherwise grassy field and hold up their hands, as if in benediction. On the right, the composition is roughly the same, although now their hands press against the massive stone.

Off in the distance, a fence is glimpsed, suggesting a cultivated landscape rather than a wild one, while a lone telephone pole identifies the rural location as tethered to community via modern communication. The photographs smartly picture the classic irresistible force paradox. What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object? Can an artist alter a deeply established cultural relationship to the natural world?

Come to think of it, in these photographs, which is the force, and which is the object — the person or the rock? Or are they interchangeable?

It takes a moment, but olagbaju’s gesture of first blessing, then touching a seemingly immovable boulder shifts your perspective, and that might be enough to generate at least incremental change. Like the steady drip-drip-drip of water on stone, which over millenniums reduces a monolith to sand, human contact will have its way.

The exhibition is not a comprehensive history of ecofeminist art. Pioneers of the genre such as Agnes Denes, who once transformed a Manhattan landfill into a wondrous urban wheat field, and Helène Aylon, who commemorated the end of the Cold War with anti-nuclear performance art, are absent. The Brick presentation is instead a provocative sketch suggesting that a museum would do well to undertake a full historical overview of ecofeminist art from the last half a century.

It’s also disappointing that no catalog accompanies the show; one is said to be in the works, but publication is not expected until next year, presumably so that new commissions, installations and mixed-media works can be documented and included. Art spaces used to deal with such complications by publishing a two-volume set — a primary one to accompany the exhibition as it opens and a small supplement to record additions. But that traditional practice seems to have fallen by the wayside.

It’s a loss. Yes, the two-tome process is more expensive to produce. Yet, for the benefit of the art audience, it should simply be regarded as necessary.

Still, smartly organized by Brick curator Catherine Taft, with curatorial assistants Hannah Burstein and Kameron McDowell, “Life on Earth” manages to cover a good deal of territory. In this contribution to the Getty-sponsored festival “PST Art: Art & Science Collide,” the breadth, both aesthetic and geographic, is wide.

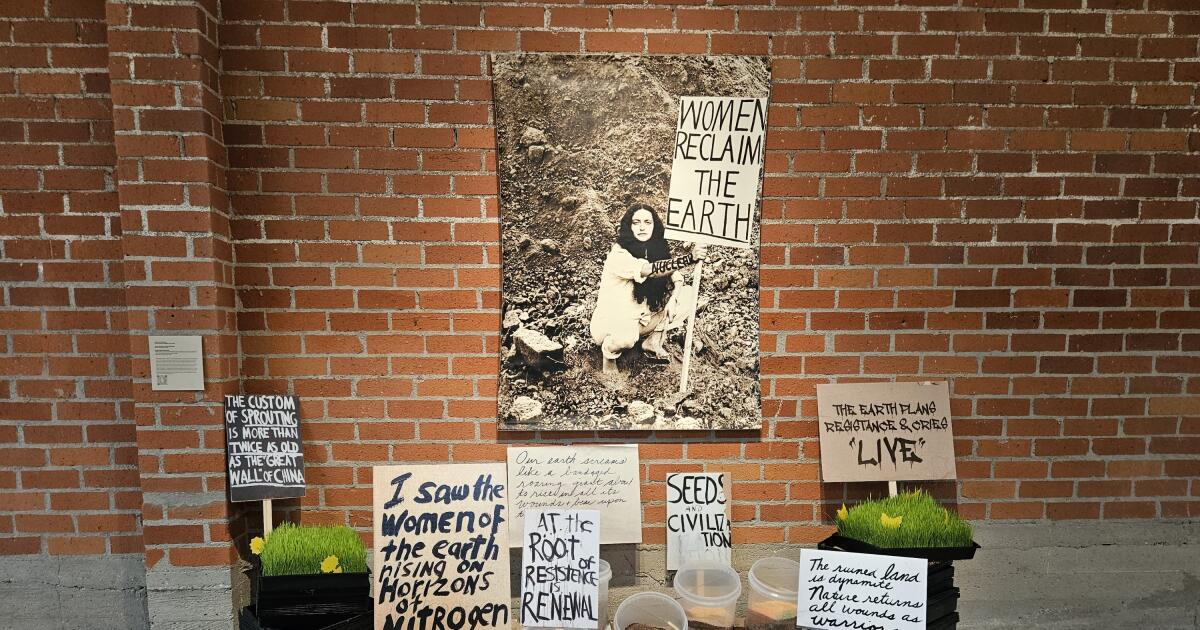

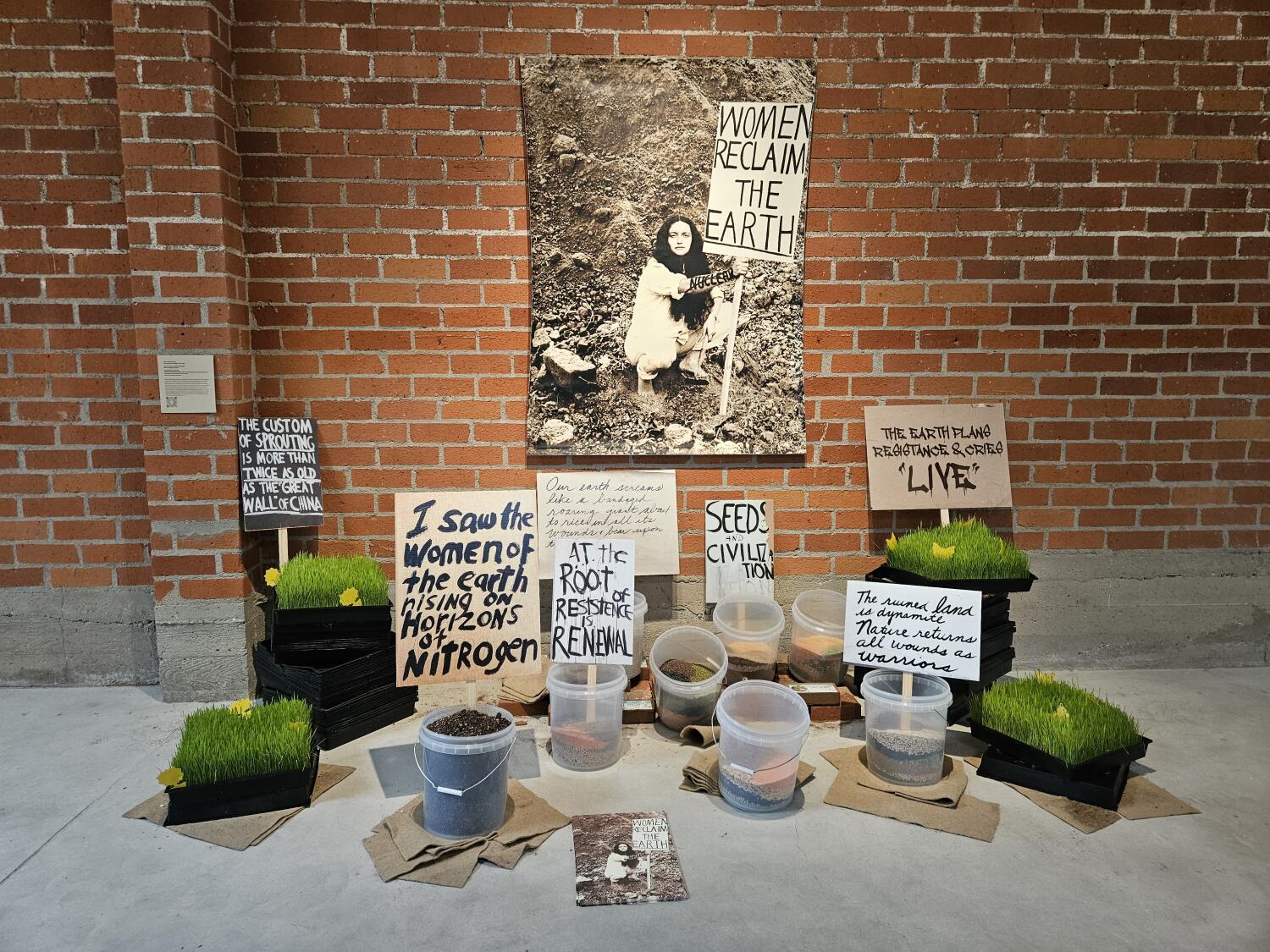

A graceful mermaid swimming around in an industrial-strength water treatment plant in Lithuanian artist Emilija Škarnulytė’s film “Riparia” becomes a perilous siren, luring the unsuspecting to the rocks. Leslie Labowitz Starus, who has operated an urban farm in Venice for decades, puts sprouts on poetic display. Carolina Caycedo carves a trio of enormous seeds — squash, beans, corn — from wood as elegant sculptural abstractions. Projected videos of rushing rivers and roiling seas mix effortlessly with disparate photographs of human gender fluidity, which marks the people in A.L. Steiner’s exuberant collage environment papering gallery walls.

Steiner’s installation helps unravel perhaps the oldest, most powerful source of the problematic fusion of nature and womanhood in ordinary cultural conceptions. The Book of Genesis doubled down not long after tagging biblical Eve as the agent of the fall from grace in the Garden of Eden. “Be fruitful and multiply,” the command then came, “and replenish the Earth, and subdue it.”

And subdue it. Subjugate women, subjugate nature. Think about that awful binary as the climate continues to change, while stormwater rises and fires burn.