In the optimistic postwar period of the 1950s, all things seemed possible, including the notion that design could make Americans live better and be better. Into this mix of new art and design in Southern California came an upstart company that focused on everyday ceramics for the Modernist mindset: Architectural Pottery.

The name may easily be mistaken for its generic, lower-case counterpart. However, “Architectural Pottery: Ceramics for a Modern Landscape,” an exhibition running through March 2 at the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona, purges visitors of that notion and helps them to realize that many of the geometric planters they’ve seen in gardens and homes over the years were the output of one dynamic company founded in Los Angeles in 1950, Architectural Pottery.

The company’s products were featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Good Design” exhibitions in the early 1950s and often shown in John Entenza’s influential Arts & Architecture magazine. The Beverly Hilton ordered 200 pieces as the hotel was being built in the mid-’50s. “Wilshire Boulevard is almost an embarrassment to us,” the company‘s co-founder, Max Lawrence, said in a 1967 L.A. Magazine article. “The plants growing in front of every major building are in our pots.”

The museum exhibition is an offshoot of a book project by Dan Chavkin, who has photographed Modernist homes across the Coachella Valley.

“He kept seeing these beautiful but radically different planters in people’s backyards,” said Jo Lauria, the exhibition’s curator. “He wrote a book proposal, with the idea of making the connection between Midcentury Modern architecture and ceramics.”

Monacelli Press accepted the proposal, and Chavkin enlisted Lauria and Jeffrey Head to do the writing for a book with the same title as the show.

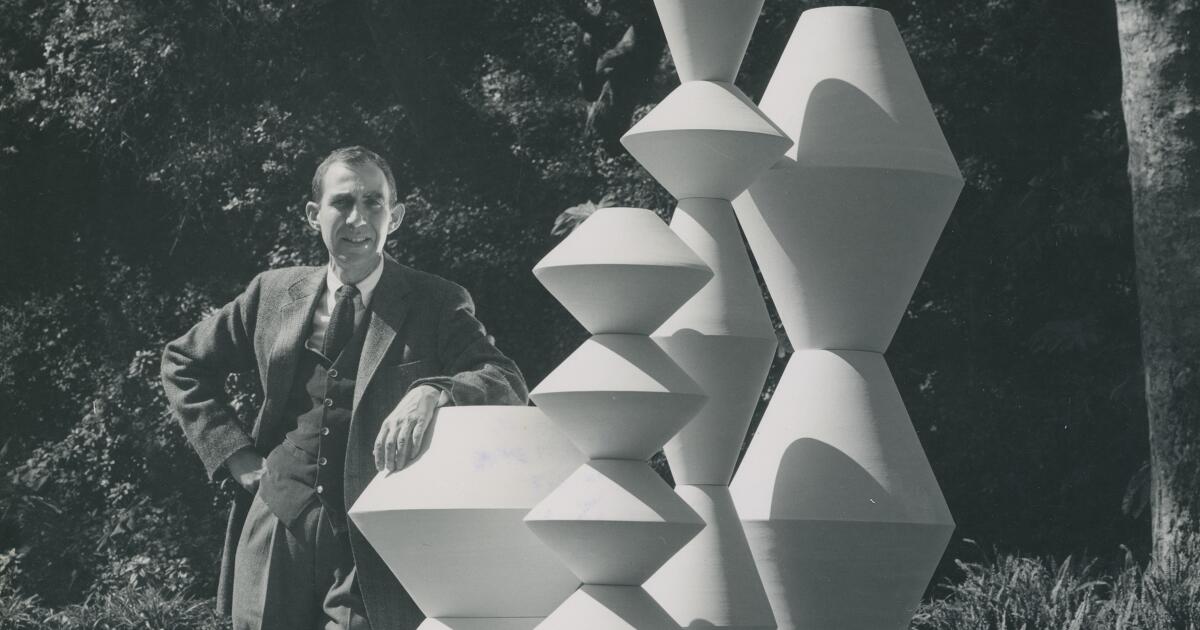

Architectural Pottery formed in 1950 as a partnership between Rita and Max Lawrence and two California School of Art grads, John Follis and Rex Goode. Follis and Goode had taken a class with LaGardo Tackett to design and market ceramic products with a modern look. Rita Lawrence, a self-described bored housewife and new mother looking for a creative project, noted that so much pottery she saw was classic Italian, Spanish or Renaissance in design and that little seemed suited for the emerging modern L.A.

Architectural Pottery launched from the Lawrences’ Gregory Ain-designed house in Mar Vista, and for years, Rita Lawrence ran the business from there before the company established an office on South Robertson Boulevard. She was president of the company, keenly involved in sales and marketing, but she also saw her role as educational. In the postwar building boom, there was a need for sand urns and planters, accent sculpture and tableware, all of which the company produced, but she also thought good modern design — open, light-filled homes connected to gardens — created a sense of optimism and well-being.

The exhibition starts with a history of the company, with photographs of the Lawrences and early collaborators, plus a photo gallery of their key designers and 3D examples of their work. Rita was particularly open to working with young potters as well as designers not versed in ceramics. Perhaps the most important employee, Lauria said, was David Cressey, who had studied ceramics with Vivika Heino at USC and Laura Andreson at UCLA. Starting in 1961, Cressey oversaw production for the company and pioneered some designs himself.

For the record:

7:29 a.m. Dec. 7, 2024An earlier version of this article misstated designer David Cressey’s first name as Bill. The date of the AMOCA panel discussion, originally stated as Jan. 6, has been updated to Jan. 12.

At the company’s factory, basic forms were mass produced through molds. Pieces could be customized with different colors, textures and configurations. Cressey developed a formula for liquid clay and experimented with overlapping glazes and new textures. He created a texture called Phoenix by repeatedly ramming the end of a 2-by-4 into wet clay.

“He had this library of molds, and then he would establish a vocabulary of textures and glazes,” Lauria said. “So at the end of the business, there were 14 textures and about 11 glazes that you could choose from.”

Walk through the exhibition, and so many of the vessels will be familiar: an hourglass form made of two cones fused together, textured bowls on simple metal stands, a large egg standing on its end — works sourced from more than 20 lenders. The objects are now highly prized collectibles that can sell for thousands on Etsy or 1stDibs. And yes, there were, and are, plenty of knockoffs. One of the weaknesses of the business was how easily its products were copied.

The exhibition design by Gary Wexler reflects the clean, Modernist look of the objects on display. A large display platform in the middle of the gallery has an undulating form and rounded corners. The design is an aesthetic choice, echoing the biomorphic shapes of some Architectural Pottery, but it’s also practical, allowing the viewer to get closer to the exhibits. Wexler also designed the book, which handsomely balances reproductions of magazine ads and catalog pages with historic shots of Architectural Pottery personnel showrooms and workshops, as well as contemporary photographs of the objects in gardens and interiors.

Follis and Goode, the designers who co-founded Architectural Pottery with the Lawrences, sold their interest in the company in 1960. Of the featured designers in the exhibition, only one is still alive: Marilyn Kay Austin, who also was the company’s only staff designer during her time there. Fresh from the University of Illinois with a degree in industrial design, she moved to California in 1962 in search of work and was introduced to Rita Lawrence.

“I’m sure that another place wouldn’t have been that quick to hire a woman,” Austin, now in her mid-80s, said in a phone interview. “It was a good place to work. I was fortunate.”

Austin began laying out Architectural Pottery advertisements and catalogs at a time when the work was cut-and-paste. She later designed sand urns and containers. Sand urns were much in demand in public spaces, she said, because so many people smoked. Because she was not a ceramicist, she drew her designs and occasionally sculpted her prototypes from foam and designers clay. She created the very popular Egg planter and was at the company for three years before she was let go. (She landed a far better-paying job at American Standard.) Now retired, Austin will be on a panel discussion at the museum on Jan. 12.

The Lawrences sold their interest in Architectural Pottery (which had become Group Artec) in 1974, and the company shut down after a 1984 fire at its Manhattan Beach manufacturing facility. Rita Lawrence died in 1999 at ago 80, and Max Lawrence lived to 98 before he died in 2010. Today, Vessel USA manufactures some of Architectural Pottery’s original designs as new generations of consumers discover the planters, pots and totems that still stand as visual signatures of midcentury modernism.

“Architectural Pottery was originated to make a statement about today’s way of life, not to imitate or adapt the past,” Rita was quoted as saying. “The forms we have introduced have become symbols of their era; the forms we will do in the future will be different, as we perceive new requirements and a new architectural idiom.”