Johnny Carson, the man who made “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” an American institution, has been off the late-night air longer than he was on it.

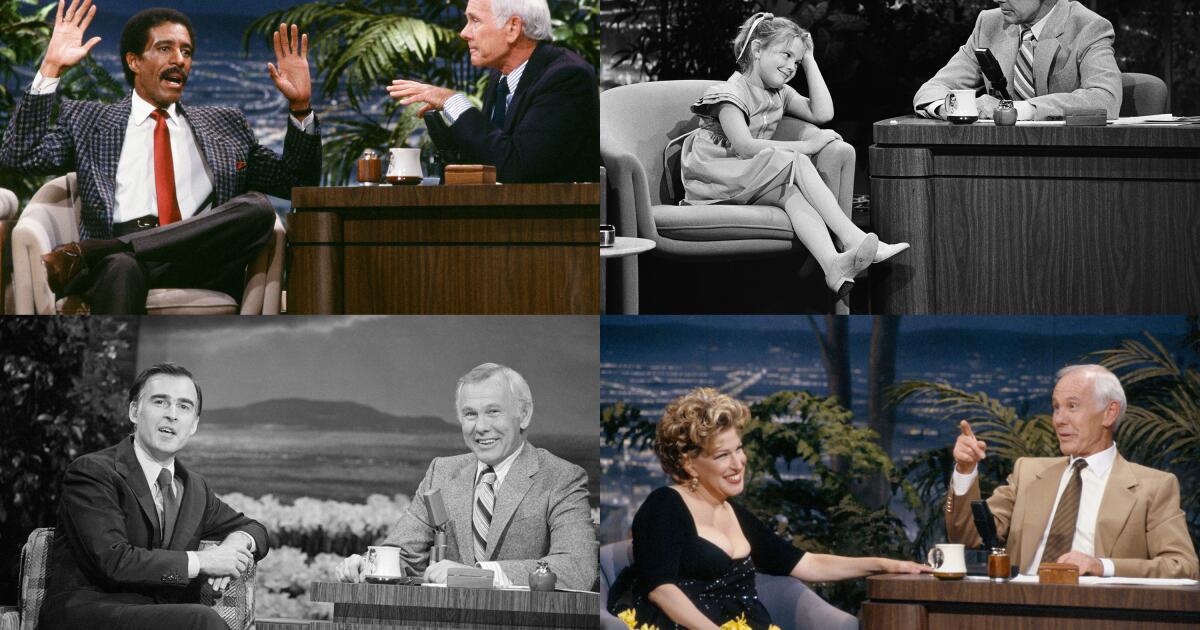

For people of a certain age — you can do the math — this is more than a little shocking. When Carson walked away from “The Tonight Show” in 1992, it was a cataclysmic cultural event. For nearly 30 years, he was television’s uber host. Cool rather than warm, mischievous rather than passionate, he all but invented the opening monologue, launched countless comedy careers (including those of David Letterman, Carson’s preferred heir, and Jay Leno, his actual replacement) and gathered millions of Americans every weekday night for a collective bedtime story. Fifty million tuned into his final appearance on “The Tonight Show.”

Now, of course, at least two generations know him mostly as a reference point to a time when an audience of 10 million was a possible nightly average for a late-night show (Stephen Colbert, current king of the time slot, averages less than 3 million). Now there are young adults who associate the iconic “Heeeeerrrrreeee’s Johnny” more with Jack Nicholson in “The Shining” than with Ed McMahon’s nightly introduction.

So perhaps the publication of Bill Zehme’s long-anticipated biography “Carson: The Magnificent,” finished by Mike Thomas, is occurring just when it should. Television continues to produce stars worthy of benedictions and analysis, but it’s difficult to imagine that any will leave as deep an imprint on his or her fans as Carson did.

If you are, or have in your life, a Johnny Carson fan, you know what I’m talking about: the formidable list of attributes that set him apart — the suits, the laid-back stance, the endlessly bobbing pencil, the lethal one-liners and raised eye-brow sangfroid that could dissolve into helpless laughter. Carson fans love to remind you that he was, for all his sleek sophistication, a Nebraska boy at heart; that he was an accomplished magician and musician; that he almost didn’t take the “Tonight Show” gig, but after he did, everyone who was anyone eventually found themselves on the sofa beside his desk.

That he was also, by his own admission, an often violent, black-out alcoholic who tore through three marriages (he was on his fourth when he died), a mostly absent father and a man who punished perceived betrayal with instant and utter banishment are often but footnotes in the tale.

And so it is in “Carson the Magnificent,” which is as much the definitive testimony of a Carson fan as it is a definitive biography, a decades-long labor of love. Of Zehme for Carson, but also of co-author Thomas for Zehme, who died in 2023 after battling cancer.

A prolific and respected celebrity biographer, Zehme regularly penned celebrity profiles for Esquire, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone and Playboy. He wrote books about Frank Sinatra and Andy Kaufman and co-authored the memoirs of Leno and Regis Philbin. For years, he threw himself long and hard against Carson’s legendary citadel of privacy and in 2002 got the first interview after Carson’s earthshaking retirement.

Three years later, after Carson’s death, Zehme began research on a biography.

He soon realized that the icon’s reputation as a Sphinx was well-deserved. In a prologue to “Carson the Magnificent,” Thomas quotes from an email Zehme sent to former “Tonight Show” writer Michael Barrie: “[Carson] was … the ultimate Interior Man, large and lively only when on camera. He was the inscrutable national monument on constant full view.”

Moreover, as Zehme writes in the first chapter, Carson’s “ghostly wrath” “seems to still spook eternal; ancient pledges of tight-lipped ones persist, especially regarding his very human flaws. ”

But Zehme kept plugging away, completing the first three-quarters of “Carson the Magnificent” before he was diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2013. After Zehme’s death, Thomas, a Chicago arts and entertainment writer and author, took on the task of completing what the New York Times had called “one of the great unfinished biographies.”

In many ways, the tale of the book’s writing reveals as much about Carson as its content. For even an experienced biographer, Johnny Carson remains the Everest of celebrity subjects — tempting and perilous.

Zehme’s research was voluminous but those looking for headline-grabbing revelations or even the salacious behind-the-scenes details of the 2013 “Johnny Carson,” written by Carson’s long-time-til-fired lawyer Henry Bushkin, will be disappointed.

For Carson fans, the biographical details will be familiar — many can be found in the very fine 2012 “American Masters” documentary “Johnny Carson: King of Late Night,” in which Zehme was featured. The book digs into early interviews with Carson and uses these, a deep reading of “The Tonight Show” and interviews with ex-wife Joanna Carson, as well as many other friends, family and co-workers, to make the case that Carson’s early and devoted love of magic — the sleight of hand, the misdirect — remained the ruling force of his life.

Jumping around in time and space, Zehme’s eagerness to make the case for the book’s title (often with breathless parentheticals) both propels the narrative and, at times, slows it down. The inevitable mix of writing styles — Zehme’s bodacious, Thomas’ straightforward — contributes an additional whipsaw effect. Still it’s a field day for anyone who remembers the likes of Kenneth Tynan and Tom Shales writing about the late-night host in a way usually reserved for poets and presidents.

More disturbing is Zehme’s willingness to underplay Carson’s lifelong habit of infidelity and his catastrophic relationship with alcohol. An emotionally withholding mother is inevitably blamed for Carson’s self-destructive matrimonial habits; the throughline of drinking exists almost in subtext.

Scenes are briefly described in which a drunk Carson decks a friend and terrorizes wives. ”Occasionally he would wake the next day to discover that some such havoc had bruised the flesh of his sons’ mothers,” Zehme writes of Carson’s first marriage before recounting a “60 Minutes” profile in which third wife Joanna Carson told Mike Wallace, “During that black out drunk phase, I was scared.”

But more emphasis is placed on Carson’s inevitable contrition, and his public admission that he “did not drink well,” than on the possibility that it might have been alcoholism, rather than a love of magic, that helped shape the very private life of the public man.

Even the tragic death of his son Rick, who died in a car accident in 1991, is given relatively short shrift. Carson’s longtime friend and band leader, Doc Severinsen, said later that “Johnny was never the same, ever, after that,” but we have only Severinsen’s word for that. (Carson did not attend his son’s funeral — according to one of Rick’s friends, Carson said he did not want the inevitable press coverage to turn the service into “a circus.”)

Zehme is too good a journalist to ignore the more troubling aspects of his subject, who was often described off-stage as cold and aloof, but he is also too big a fan, perhaps, to explore them fully.

Early on in the book, Zehme compares Carson to Sinatra, two men who touched their audiences deeply, often at difficult moments. “Sinatra brilliantly offered the jolt of emotional solidarity in performance whereas Carson specialized in dangling forth an emotional distraction … prompting improbable laughs at times when you thought you would never laugh again.”

The difference is that while Sinatra’s voice remains omnipresent in modern life, “the ephemeral magic of Johnny Carson, who loomed just as large and swung just as mightily … no longer hums and flickers into nightscape ambiance.”

“Carson the Magnificent” is the offering of an acolyte who saw in Carson, as many did, a man who “launched the dreams of generations, as no golden Hollywood dream merchant might have fathomed, even in metaphor. Never a movie star, he shone maybe bigger anyhow.”

Zehme, with Thomas’ help, was determined that the world not forget.

Mary McNamara is the Pulitzer Prize-winning culture columnist and critic for The Times.