Legislatures in 16 states, Florida prominent among them, have been deliberating rolling back child labor laws. In some cases, major steps have already been taken to loosen restrictions on work by kids as young as 14. The erasures, almost exclusively promoted by Republicans, target legal prohibitions against child exploitation that have been in place for nearly a century.

Here’s a surprise: Radical transformations in photography are one primary reason the threatened rollbacks have gotten traction.

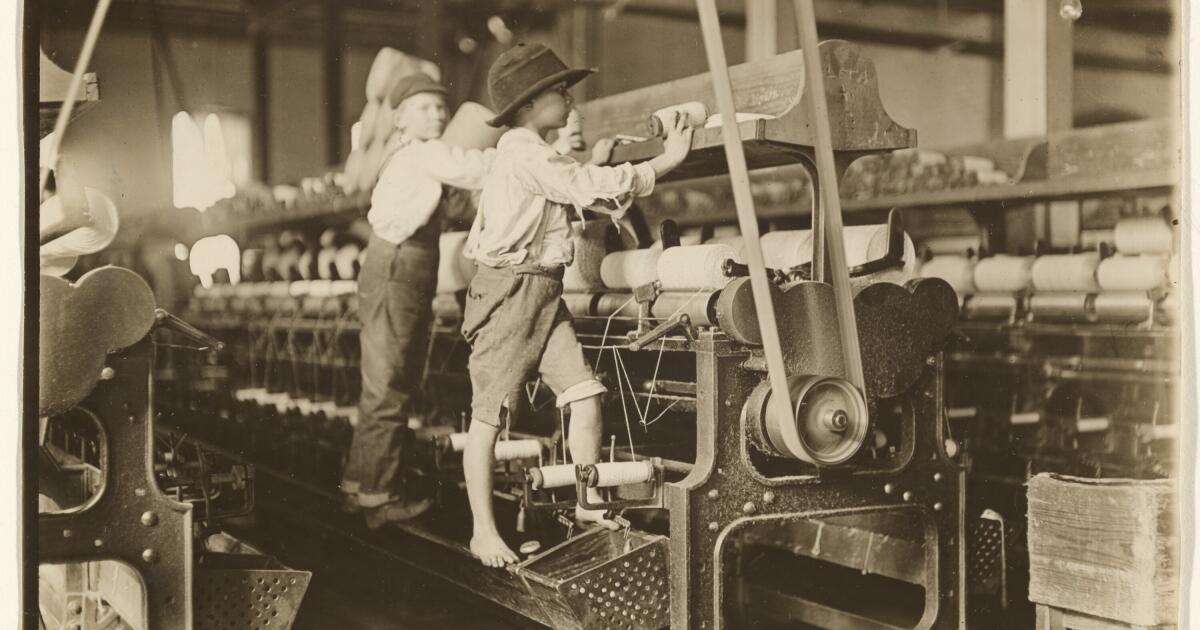

In the first decade of the 20th century, sociologist Lewis W. Hine (1874-1940) picked up a camera and trained it on the cheap labor performed by children, which had become commonplace everywhere from Pittsburgh steel mills to Carolina textile factories, from an Alabama canning company for shucked oysters to West Virginia factories for glass. When published, Hine’s haunting pictures scandalized America, and laws to protect kids emerged.

An entire modern artistic genre — documentary photography — was weaned on the growing social effort to rein in the abusive practice of forcing children to toil in sweatshops and on farms in the wake of the Gilded Age. Emblematic is Hine’s luminous picture of a young girl — called a spinner — at North Carolina’s Whitnel Cotton Mfg. Co. He positioned the shabbily dressed child between a seemingly unending row of whirling textile bobbins, where her job was to patrol the interminable line and speedily repair broken threads, and a row of factory windows where light streams in from outdoors to illuminate the interior scene. She has stopped her work to face the camera, clearly at the photographer’s instruction.

Her right hand, fingers curled, rests on the infernal machine, while her left hand is open on the windowsill. She’s a juvenile hostage, an innocent trapped between captivity and freedom.

A spinner’s toil in a textile mill was not especially dangerous, although loss of a finger was certainly a risk. However, as Stanford art historian Alexander Nemerov has sharply observed, the damage recorded in Hine’s entrancing photograph was inflicted at least as much on the young girl’s soul as on her body. An aura of entrapment is evoked. A repetitive, tedious, mechanically determined routine is her present and her future, stretching into infinity. When her focused gaze meets yours, a coiled look of resignation stiffens her soft face, and it is painful to see.

You might move on. But for her, this is it.

The transformation in photography today is not that artists have abandoned a productive interest in the state of the world, including these sorts of cruel labor conditions, which social documentary photographs explore. They haven’t. LaToya Ruby Frazier is one impressive example.

“The Last Cruze,” her moving exhibition at Exposition Park’s California African American Museum in 2021, registered the lives of union workers at the General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio — workers displaced and disrupted when the factory was shuttered two years earlier. Frazier’s installation of 67 black-and-white photographs and one color video told an unflattering story of the human aftermath, and it did so in fascinating ways.

But it is also fair to say that her soulful installation did not — could not — generate the same sort of outrage that Hine’s photographs did. In 1908, when he began to publish his images of young children working under bleak conditions in factories and on farms, the context in which the pictures appeared was radically different from today’s visual environment.

Simply put, photographs were still scarce, relatively speaking, but they were on their way to replacing woodblock illustrations in newspapers and periodicals to become the dominant form of visual media. Camera pictures were disruptive. They connected straight to the world in front of the lens, and they had the capacity to grab eyeballs, pulling minds along with them.

Today, living in a media-saturated landscape, there’s no escape from them. Only rarely do they disrupt. Wake up in the morning, check your phone, and scores — maybe even hundreds — of pictures flash by before breakfast. In such a milieu, Hine’s troubling 1908 photographs would easily disappear, perhaps seizing a moment but soon evaporating into the visual miasma that floods the zone daily.

And now, with the advent of artificial intelligence, assumption of a direct connection to reality unravels. Skepticism about photographic authenticity arises.

Hine, then in his early 30s, was part of a growing Progressive movement that sought large-scale social and political reform following the collapse of post-Civil War Reconstruction and the explosion of the grasping Gilded Age. John Spargo, a self-educated British stonemason who emigrated to New York in 1901, became an unlikely political theorist of the movement. His book “The Bitter Cry of the Children” fiercely condemned child labor practices, arguing in part that interrupting school with work caused lifelong impairment.

Novelists as different as Jack London and H.G. Wells agreed, and they said so in short stories and magazine essays. A private, nonprofit National Child Labor Committee formed to lobby state and federal officials, while embarking on public education. The NCLC hired Hine.

His research experience as a sociologist had led him to the pioneering photographs of Jacob Riis, a police reporter for the New York Tribune. Riis exposed Lower East Side slum conditions in tenement photographs that would form the basis for his renowned book, “How the Other Half Lives.” Hine, recognizing the power of photographs as visual evidence, soon picked up the camera too.

His pictorial documents of child labor began to appear in weekly magazines, like Charities and the Commons, and in widely distributed NCLC pamphlets with such dry if explanatory titles as “Child Labor in Virginia” and “Farmwork and Schools in Kentucky.” The publications might have had limited circulation, but their poignant photographs seeped into the popular press.

For readers who did not spend their days walking the factory floor or supervising the sorting of coal chunks sliding down a chute, an incisive picture would stand out. Witnessing a photograph of a naive child climbing up barefoot into massive machinery or shadowed beneath big tobacco leaves sprayed with pesticides could easily stick in the mind.

Hine’s 1917 picture of a 10-year-old boy working Connecticut’s Gildersleeve tobacco farm, south of Hartford, shows him on his knees in an irrigation ditch between rows of what is probably the tough tobacco used for cigar wrappers. (More tender tobacco, shredded for the filling, was grown in the South, not New England.) It’s the first picking, when three fully grown leaves near the bottom of the stalk are cut and stacked. First one side’s plant, then the other’s, would be picked — and on the child would go, plant by plant in the humid, late-summer heat down lengthy rows covering acres of farmland.

Soon, the second tier of leaves would mature and the process repeated. Then the third tier was ready, picked while reaching up, and so on until, standing, the plant was fully harvested.

The labor’s grueling tedium is stifling. My own first summer job as a kid in search of after-school pocket money was picking cigar tobacco on a Connecticut farm just north of Hartford. I was 14. I lasted less than a week. Hine’s tousled little boy, who looks forlornly into the camera with scowling dark eyes beneath a furrowed brow, likely had no such liberating choice.

Today’s drive to roll back state child labor laws is being pushed by conservative groups like the Foundation for Government Accountability in Naples, Fla., a well-funded anti-welfare organization. (Ironically, according to its 2023 tax filing, the CEO of the FGA, a nonprofit seeking to loosen child labor restrictions, received more than $498,000 in salary and other compensation.) In that tourism-dependent state, the Orlando Weekly reported that Gov. Ron DeSantis’ office wrote his state’s bill, saying changes made by the legislature last year to loosen working restrictions for minors “did not go far enough.” If passed, teenagers as young as 14 could work overnight hours on school nights or long shifts without a meal break.

The Miami Herald reported that, in defense of his plan, the governor explained to the Trump administration’s border czar that a younger workforce could be part of the solution to replacing “dirt cheap” labor from migrants in the country illegally. The bill, he added, would “allow families to decide what is in the best interest of their child.”

DeSantis asked, “Why do we say we need to import foreigners, even import them illegally, when you know, teenagers used to work at these resorts; college students should be able to do this stuff.”

College students, of course, are adults, not children, their average age between 18 and 25. And the Child Welfare League of America notes that, in 2022, parents committed 71% of reported child abuse in Florida, so an appeal to family decision-making as a replacement for laws regulating child labor is fraught.

The historical example of Lewis Hine’s exceptional documentary photographs — and their beneficial impact on children’s lives — would help illuminate the current, highly contentious subject. His work is found in many public collections. The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y., are two that hold thousands of prints and negatives. The Getty Museum in L.A. has more than 100.

But there’s a hitch: However much art museums today express a commitment to social relevance, their programming is the opposite of nimble. It takes years to produce and schedule an exhibition. Today’s child labor fight might be over.

If ever there were a vital reason for a virtual show on an art museum’s website to be presented and vigorously promoted, this is it. During the first Trump administration, the popular digital magazine Bored Panda did just that, mounting an extensive anthology of Hine’s riveting child labor photographs. Demand for cheap labor never goes away, but sometimes it crests. We’re there again.